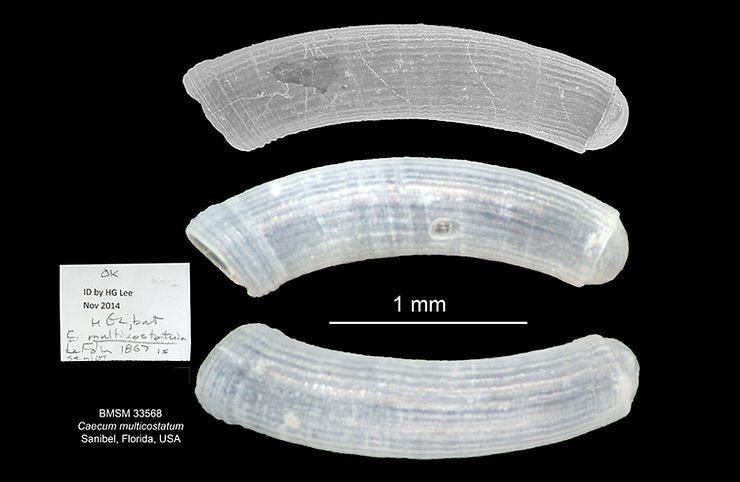

Shell of the Week: The Multicostate Caecum

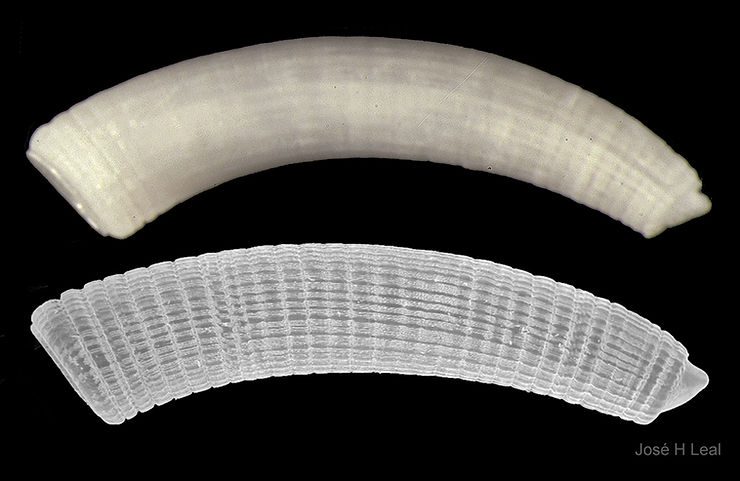

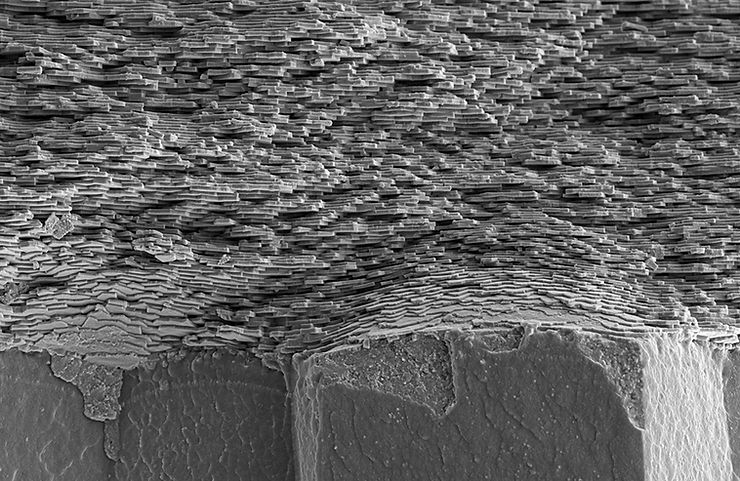

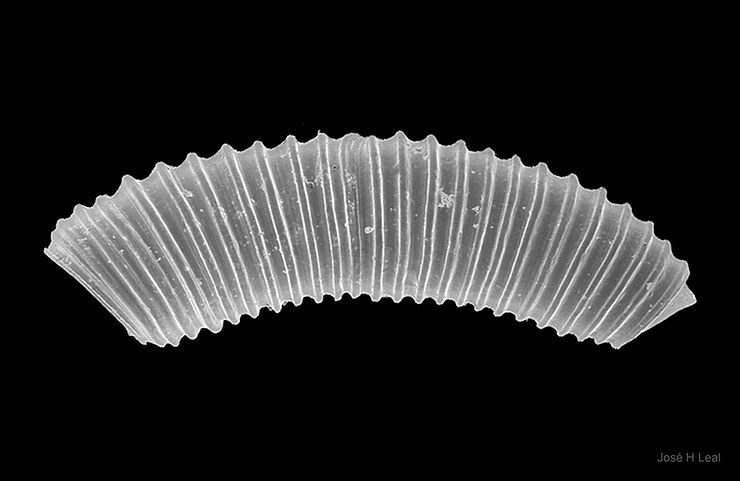

Another small (and neglected) local species of the family Caecidae (the caecums), Caecum multicostatum de Folin, 1867 has a tubular shell that rarely reaches beyond 2 mm (about 0.08 inch). The shell sculpture in this species shows a number of lengthwise, delicate ridges. The shell aperture (opening) is encircled by ring-like cords. The shell "plug" is blunt, hemispherical. The shell color is white or tan. The top image was taken with a Scanning Electron Microscope. #caecummulticostatum #caecidae