Cowries are Cool!

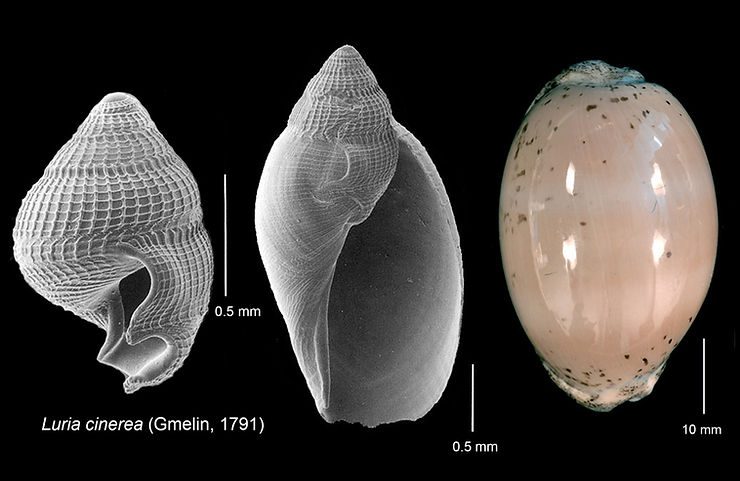

Throughout human history, the enjoyment of shells and curiosity they spark have been the foundation for the science and better understanding of mollusks. And no other group of shells evokes more interest and appreciation than cowries (family Cypraeidae). Their “egg-shaped” shells are usually smooth, glossy, and their weight “feels” just right when held in one's hand. From time to time the living snail covers the shell from both sides of a slit-like opening, and the shell-making mantle repairs bl