The Enigma of Hidden Colors

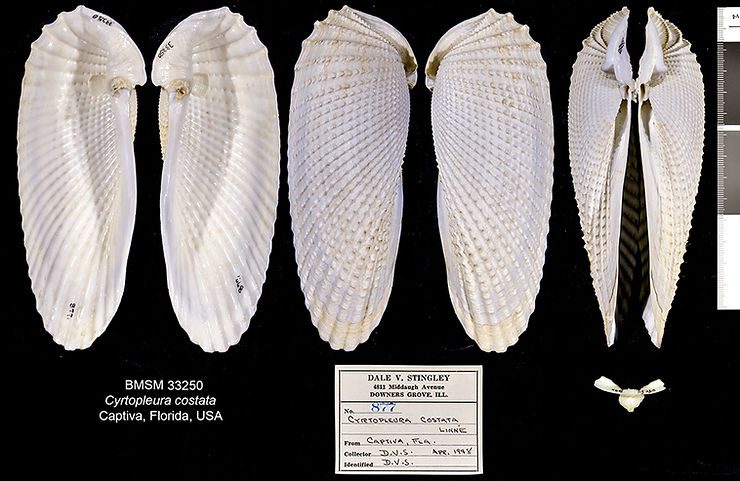

Colors in animals are almost always linked to visual behaviors and species interactions. Bright colors and patterns on mollusks may help, for instance, attract a mate, warn a predatory fish of a foul-tasting or poisonous sea slug, or camouflage a snail against its habitat. We expect that most colors “serve a purpose” based on another animal, “friend or foe,” being able to see those colors. But what if pigments are present inside a clam shell, in an area that is never seen by another animal? Take