Shell of the Week: The Two-tooth Barrel Bubble

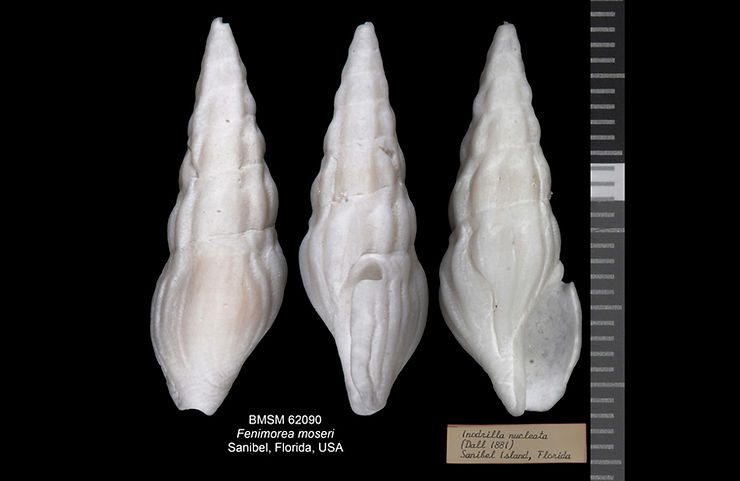

Giving continuity to our discussion of the local barrel bubbles, today I want to introduce the Two-tooth Barrel Bubble, Cylichnella bidentata (d’Orbigny, 1841). This small snail reaches 4 mm (0.16 inch), has a characteristic sunken spire, and the columella (viewed on the left side of the aperture, or opening) with two folds that at a glance look like two “teeth.” The aperture is flared in anterior direction (on bottom of the picture.)